What privacy means to me: The fried egg approach

For many people, privacy means barrier. Especially in mental health, our society has treated information with secrecy and stigma. As health care providers work to create acceptance and compassion for those suffering from mental illness, our approach to privacy needs to shift as well. See links to new policies, resources and education event at the end of this article.

Redefining the Circle of Care

Most providers are familiar with the concept of sharing information within the “circle of care”–you don’t need consent to share client information with other health care providers who need to know.

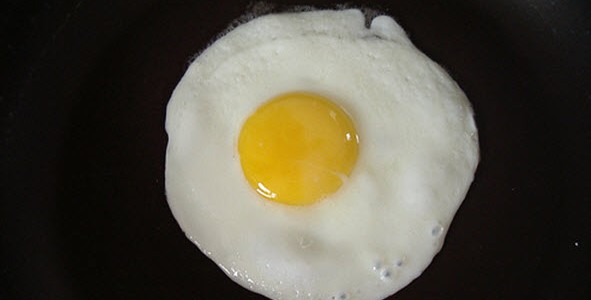

Think of the circle of care as a fried egg. Health care providers within your organization are the yolk – an inner circle where necessary information is freely shared, either through team meetings or through access to clinical information systems. Then there’s the white – health providers outside the organization and other care providers needing the information for similar purposes.

Family members are in the circle of care; where they provide support and care to our clients they should receive the information they need to do so.

The police, in their role as first responders to those with mental illness and/or addiction, are also in the circle of care. We are working on an information sharing agreement with police so that when police bring patients to our hospitals under the Mental Health Act, information may be shared between police and health care providers for the common purposes of assessing risk to the person’s own safety or the safety of others and to provide appropriate care, response and service to that person.

Reach out to others when you have concerns

Sometimes clients tell us they do not want information shared with a specific care provider or with family members. Where the client is capable of giving consent, we must respect these wishes (although we may point out the value of including family members as part of the care team). But where withholding information could be dangerous to the client or to others, it may be necessary to disclose need-to-know information in spite of the client’s wishes. This may involve sharing concerns with family members, with other agencies that provide services to the client, or with the police where it is in the best interests of the health and safety of the client or others.

It can be very difficult deciding when to share information because you are concerned about someone’s health or safety. It takes a lot of courage to report such situations. Staff do not have to make these decisions alone, but can consult with their supervisors, managers, Client Relations and Risk Management, and the Information Privacy Office. Even more importantly, staff should know that when in an emergency they make a good faith decision about sharing information, they will be supported by their organization.

It’s privacy, not secrecy

In the past privacy messages have left healthcare providers feeling uncertain about what they can communicate and afraid of repercussions if they communicate too much. Now it’s time to support health care providers in the wonderful and compassionate care they provide by changing the way we think about privacy.

New policy and resources

- VCH has a new Family Involvement With Mental Health and Addictions Services Policy which recognizes the importance of collaboration amongst clients, families and care providers for better client outcomes.

- VCH has also recently revised its Release of Information and Belongings to Law Enforcement Policy to provide more clarity and direction on sharing information with police.

- A new Quick Reference Guide on Disclosure of Personal Information to Law Enforcement helps guide staff through different scenarios that may arise.

What’s next

VCH is working on information sharing agreements with the VPD and other law enforcement agencies so that hospitals and police can respond with appropriate care and treatment for those suffering from mental illness.

Education Event

What does privacy mean to you?

Monday September 23, 2013

8:30 a.m. – 12:00 p.m.

Paetzhold Auditorium, Vancouver General Hospital