Healing through Indigenous art

At the end of June, VGH & UBC Hospital Foundation and Aboriginal Health hosted an event to showcase the art of Paul Windsor, an Haisla Heiltsuk artist whose nine acrylic-on-canvas panels have been added to the VGH collection on display in the Sassafras cafeteria on the third floor of the Jim Pattison Pavilion. The event featured a conversation between Paul and Dana Claxton, renowned Lakota Sioux artist and UBC Associate Professor of Visual Art, looking at health and healing through Indigenous art.

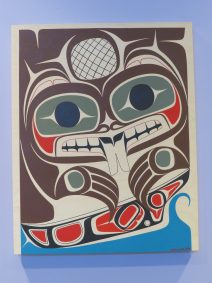

Paul is from the Heiltsuk/Haisla Nations and was born in the coastal community of what is now Kitimat. He is from the Blackfish or Killerwhale Clan. The Haisla social system is based on matrilineal clans. Eight clans (Eagle, Beaver, Crow, Killer Whale, Wolf, Frog, Raven, and Salmon) make up the community, each clan with its own chief. This clan membership influences Paul’s work. He has spent time connecting to the land and ocean and has a deep respect for the voice, grace and power of animals in their natural kingdom. He draws inspiration from their spirit and feels connected to them through his ancestry. The nine panels on display each feature a different fish, mammal, amphibian or bird, representing the sea, land and sky.

“We coexist and have a direct relationship through love and respect that animals have a right to live, flourish biologically and spiritually. They need a place to live and we need to have as low a carbon footprint, as low of an impact as we can. That is the tradition of my people – be there, exist, don’t destroy. That’s where the art stems from.”

The European idea of art as a material good used as a commodity, as sellable or collectible, is very different from the Indigenous views of art. In fact, as Dana Claxton pointed out, there is no word for art in North American Indigenous languages. The paintings, carvings, beadwork and weaving created by Indigenous artists have had a purpose and intention behind them. These ‘art’ works were used to identify one’s location, to tell a story, to show what’s gone on before, as a description of a relationship or as an expression of feelings. In essence they are an expression of Indigenous culture; and for Paul, part of his artistic journey is to reclaim his cultural identity.

The feelings and energy Paul puts into his work are what he hopes viewers will feel and take from it; the positivity and vibrancy of the colours – bright red, green and blue and the lively physical expressions of mammals, fish, amphibians and birds offering a message of hope, connectedness and healing.

For visitor Ernest, an Elder who had come down to VGH from the Lake Babine Nation and was in the hospital visiting his nephew when he came across the event, it was this message of healing that he took to heart. His nephew had fallen from the top of bleachers and had sustained a broken neck and spinal injury. Away from his home and nation, he recognized his Frog Clan in the art work on the wall and was touched by this recognition. This is what Paul intended with these images: to bring a small part of Indigenous culture into the hospital to comfort patients and their families during their healing journey.

It was the result of the historical destruction of identity for First Nations people in Canada from the government’s measures such as the ban on potlatch, instituting the reserve and residential school systems, and the death of languages and cultures, that growing up Paul saw his friends and family members hurting, confused and wounded. There were a lot of suicides and he wondered why people were killing themselves. As a young adult Paul also had his own addiction issues. Now sober, married and with a son of his own, he is able to take what he lived through and make something positive through his artwork. “These are sober, healthy pieces for the children, the next generation. I hope when people look at these pieces they will think of hope for the future, so much about BC Aboriginal art is about our children, our future.”